Gordon Bennett Trophy (aeroplanes) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Gordon Bennett Aviation Trophy is an international airplane racing trophy that was awarded by

Following the success of the Gordon Bennett balloon competition, which had become the most important competition for the sport, Gordon Bennett announced a competition for powered aircraft in December 1908, commissioning a trophy from André Auroc, the sculptor who had created the trophies for both the balloon and automobile competitions. Formulation of the competition rules was entrusted to the Aéro-Club de France. It was decided that each competing nation would be allowed to field a team of three competitors.

The 1909 competition was held as part of the

Following the success of the Gordon Bennett balloon competition, which had become the most important competition for the sport, Gordon Bennett announced a competition for powered aircraft in December 1908, commissioning a trophy from André Auroc, the sculptor who had created the trophies for both the balloon and automobile competitions. Formulation of the competition rules was entrusted to the Aéro-Club de France. It was decided that each competing nation would be allowed to field a team of three competitors.

The 1909 competition was held as part of the

The selection trial for the French team was held on the first day of the Grande Semaine d'Aviation. Hampered by gusty winds and rain which turned the grass flying-field to glutinous mud, many of the twenty entrants were unable to take off, and none managed to complete the necessary two laps.

The selection trial for the French team was held on the first day of the Grande Semaine d'Aviation. Hampered by gusty winds and rain which turned the grass flying-field to glutinous mud, many of the twenty entrants were unable to take off, and none managed to complete the necessary two laps.

Air Racing History - ESPA Racing

The Big Race of 1910 , Air & Space Magazine

Air races Air racing Aviation awards Bennett family Newspaper events 20th-century awards Sports trophies and awards

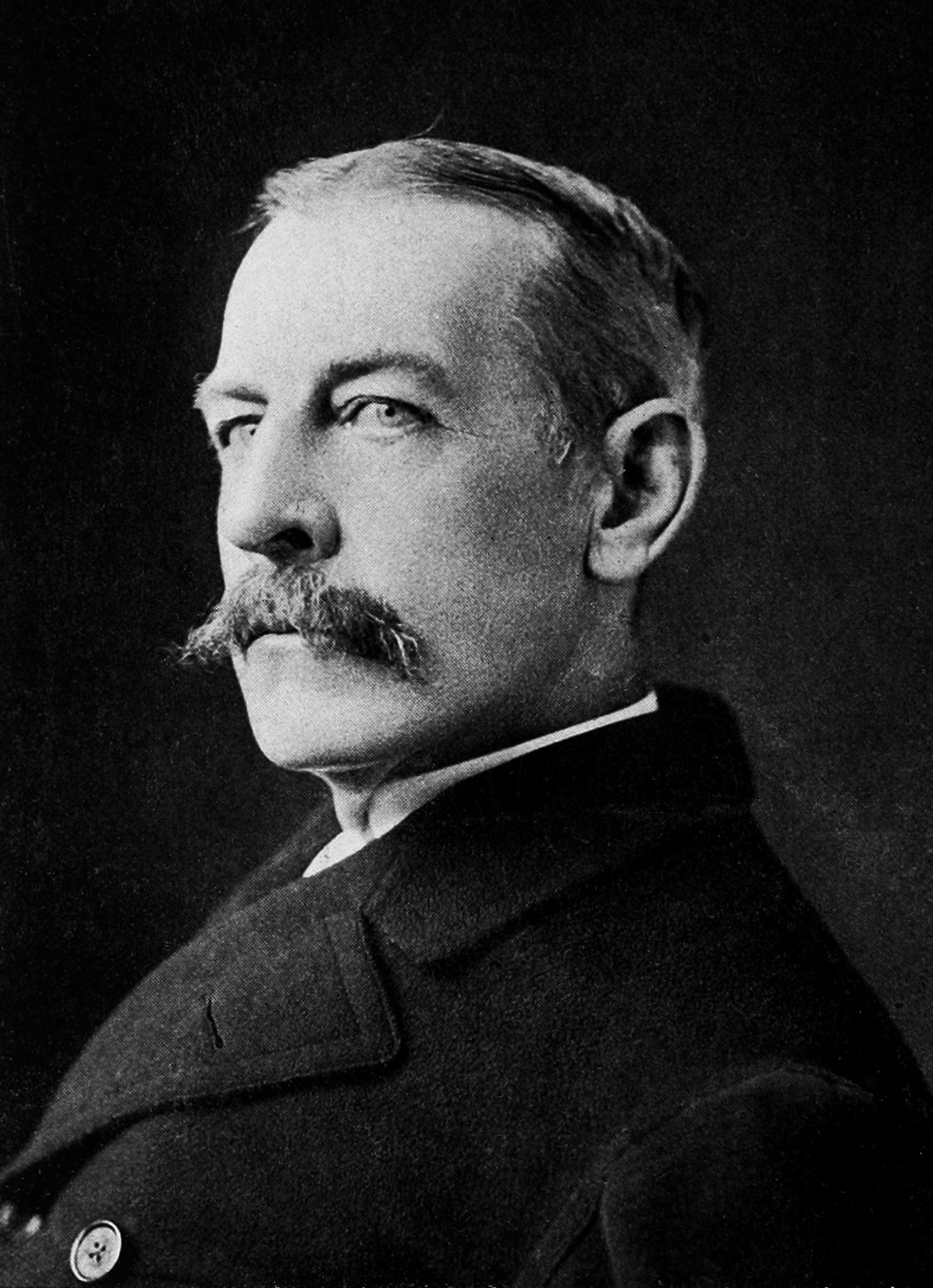

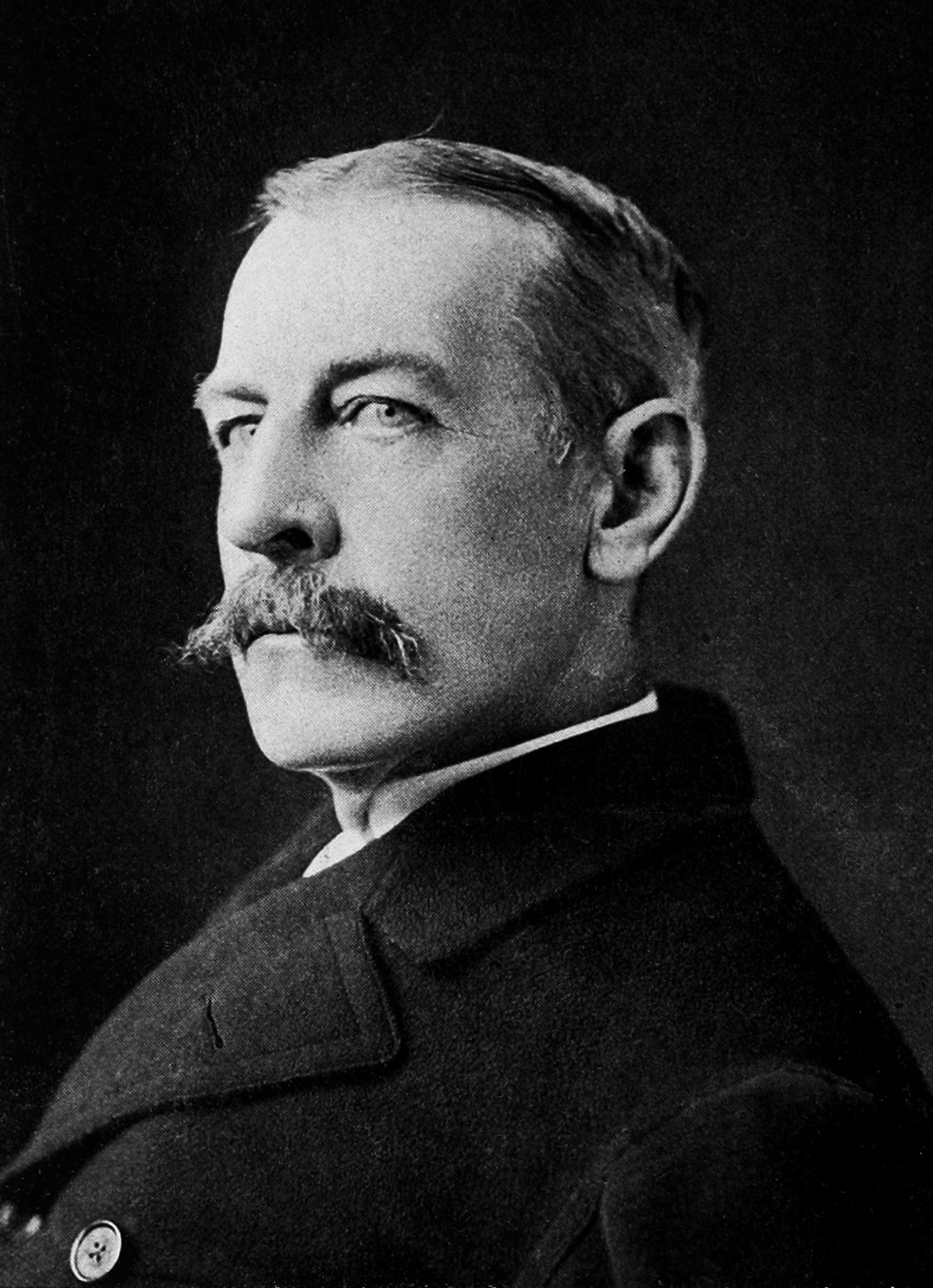

James Gordon Bennett Jr.

James Gordon Bennett Jr. (May 10, 1841May 14, 1918) was publisher of the ''New York Herald'', founded by his father, James Gordon Bennett Sr. (1795–1872), who emigrated from Scotland. He was generally known as Gordon Bennett to distinguish him ...

, the American owner and publisher of the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

His ...

'' newspaper. The trophy is one of three Gordon Bennett awards: Bennett was also the sponsor of an automobile race

Auto racing (also known as car racing, motor racing, or automobile racing) is a motorsport involving the racing of automobiles for competition.

Auto racing has existed since the invention of the automobile. Races of various sorts were organi ...

and a ballooning competition.

The terms of the trophy competition were the same as those of the Schneider Trophy

The Coupe d'Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider, also known as the Schneider Trophy, Schneider Prize or (incorrectly) the Schneider Cup is a trophy that was awarded annually (and later, biennially) to the winner of a race for seaplanes and flying ...

: each race was hosted by the nation which had won the preceding race, and the trophy would be won outright by the nation whose team won the race three times in succession. Accordingly, after Joseph Sadi-Lecointe

Joseph Sadi-Lecointe (1891 – 1944) was a French aviator, best known for breaking a number of speed and altitude records in the 1920s.

Biography

Sadi-Lecointe was born on 11 July 1891 at Saint-Germain-sur-Bresle. He learned to fly at the Ze ...

's victory in 1920 the Trophy became the permanent possession of the Aéro-Club de France

The Aéro-Club de France () was founded as the Aéro-Club on 20 October 1898 as a society 'to encourage aerial locomotion' by Ernest Archdeacon, Léon Serpollet, Henri de la Valette, Jules Verne and his wife, André Michelin, Albert de Dion, ...

.

History

Following the success of the Gordon Bennett balloon competition, which had become the most important competition for the sport, Gordon Bennett announced a competition for powered aircraft in December 1908, commissioning a trophy from André Auroc, the sculptor who had created the trophies for both the balloon and automobile competitions. Formulation of the competition rules was entrusted to the Aéro-Club de France. It was decided that each competing nation would be allowed to field a team of three competitors.

The 1909 competition was held as part of the

Following the success of the Gordon Bennett balloon competition, which had become the most important competition for the sport, Gordon Bennett announced a competition for powered aircraft in December 1908, commissioning a trophy from André Auroc, the sculptor who had created the trophies for both the balloon and automobile competitions. Formulation of the competition rules was entrusted to the Aéro-Club de France. It was decided that each competing nation would be allowed to field a team of three competitors.

The 1909 competition was held as part of the Grande Semaine d'Aviation

The ''Grande Semaine d'Aviation de la Champagne'' was an 8-day aviation meeting held near Reims in France in 1909, so-named because it was sponsored by the major local champagne growers. It is celebrated as the first international public flying e ...

held at Reims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

in France, and consisted of two laps of a circuit. Like the subsequent competitions, it was not a direct race, but a time trial, with competitors taking off separately. As aircraft became faster and their engines more reliable, the distance to be covered was increased each year.

The last competition was held in 1920 in the French communes

The () is a level of administrative division in the French Republic. French are analogous to civil townships and incorporated municipalities in the United States and Canada, ' in Germany, ' in Italy, or ' in Spain. The United Kingdom's equi ...

of Orléans and Étampes. Unlike those held before the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

which were over short courses marked by pylons, the competition was held between two points apart because of the growing speed of aircraft. Joseph Sadi-Lecointe

Joseph Sadi-Lecointe (1891 – 1944) was a French aviator, best known for breaking a number of speed and altitude records in the 1920s.

Biography

Sadi-Lecointe was born on 11 July 1891 at Saint-Germain-sur-Bresle. He learned to fly at the Ze ...

won in a time of 1 hour, 6 minutes and 17.2 seconds, while fellow French aviator Bernard de Roumanet finished second in a time of 1 hour, 39 minutes and 6.9 seconds.

Competition winners

The 1914 race was to have been held at Reims between 19 September and 28 September, but was cancelled due to the outbreak of the First World War. There was no contest in 1919.1909

The selection trial for the French team was held on the first day of the Grande Semaine d'Aviation. Hampered by gusty winds and rain which turned the grass flying-field to glutinous mud, many of the twenty entrants were unable to take off, and none managed to complete the necessary two laps.

The selection trial for the French team was held on the first day of the Grande Semaine d'Aviation. Hampered by gusty winds and rain which turned the grass flying-field to glutinous mud, many of the twenty entrants were unable to take off, and none managed to complete the necessary two laps. Eugène Lefebvre

Eugène Lefebvre (4 October 1878 – 7 September 1909) was a French aviation pioneer. He was reportedly the first stunt pilot,

Villard, Henry Serrano, ''Contact! The Story of the Early Birds,'' 1968, Thomas Y. Crowell, ASIN: B001G8D7K0, retr ...

, flying Wright biplane

The ''Wright Flyer'' (also known as the ''Kitty Hawk'', ''Flyer'' I or the 1903 ''Flyer'') made the first sustained flight by a manned heavier-than-air powered and controlled aircraft—an airplane—on December 17, 1903. Invented and flown b ...

put up the best performance, nearly completing the course; Louis Blériot

Louis Charles Joseph Blériot ( , also , ; 1 July 1872 – 1 August 1936) was a French aviator, inventor, and engineer. He developed the first practical headlamp for cars and established a profitable business manufacturing them, using much of th ...

, who had managed to fly about 2.5 km in a Blériot XI

The Blériot XI is a French aircraft of the pioneer era of aviation. The first example was used by Louis Blériot to make the first flight across the English Channel in a heavier-than-air aircraft, on 25 July 1909. This is one of the most fam ...

put up the next-best performance. It was decided that the third place would be given on the basis of performance in the speed competition to be held that afternoon, and was taken by Hubert Latham

Arthur Charles Hubert Latham (10 January 1883 – 25 June 1912) was a French aviation pioneer. He was the first person to attempt to cross the English Channel in an aeroplane. Due to engine failure during his first of two attempts to cross ...

.

The Wrights themselves had passed on an invitation to compete at Reims, though it seemed awkward since the Gordon Bennett Trophy was crowned with a large replica of a Wright Flyer. The Aero Club of America

The Aero Club of America was a social club formed in 1905 by Charles Jasper Glidden and Augustus Post, among others, to promote aviation in America. It was the parent organization of numerous state chapters, the first being the Aero Club of New E ...

, which had sponsored the Scientific American trophy won by Curtiss a year earlier, turned to him. His aircraft was not as well developed as the Wright machines and while it was more maneuverable than the European aircraft, it was not nearly as fast. Despite this disadvantage, in the race for the cup on August 28, 1909, Curtiss won in 15 minutes and 50.4 seconds. Blériot finished second place with a time of 15 minutes and 56.2 seconds, 5.8 seconds more than Curtiss.

1910

The 1910 competition was held at theBelmont Park

Belmont Park is a major thoroughbred horse racing facility in the northeastern United States, located in Elmont, New York, just east of the New York City limits. It was opened on May 4, 1905.

It is operated by the non-profit New York Racin ...

racetrack in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

as the culminating event of a week-long aviation meet. The 5 km course marked out for the competition attracted strong criticism from the competing pilots. Alfred Leblanc

Alfred Leblanc (13 April 1869 – 22 November 1921) was a pioneer French aviator.

Biography

He was born on 13 April 1869 in Paris. In 1888, he became the technical director of the Victor Bidault metal foundry. A keen sportsman, he was an ener ...

, captain of the French team, described it as a death-trap because of the obstacles which would hinder any pilot trying to make an emergency landing, and a tight turn less than 30 m (100 ft) from one of the grandstands was christened "Dead Man's Corner" by the press. However, the race proceeded as planned.

Contestants were permitted to start at any time during a seven-hour period on the day of the race. Claude Grahame-White was first to take off at 8:42, flying a Blériot XI powered by a 100 hp Gnome Double Omega and completing his first lap in 3 minutes 15 seconds. He was followed by Alec Ogilvie

''For the businessman, see Alec Ogilvie (businessman).''

Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander "Alec" Ogilvie CBE (8 June 1882 – 18 June 1962) was an early British aviation pioneer, a friend of the Wright Brothers and only the seventh British person ...

flying a Wright Model R

The Wright Model R was a single-seat biplane built by the Wright Company in Dayton, Ohio, in 1910. Also known as the Roadster or the Baby Wright, it was designed for speed and altitude competitions.

Design

The Wright Model R was derived from the ...

at 9:08 and Alfred Leblanc at 9:20. Leblanc, who was the chief pilot for the Blériot company, was flying a 100 hp Blériot XI differing slightly from Grahame-White's, with a different propeller and a reduced wingspan. Leblanc's aircraft was clearly faster: after four laps his time was 1 minute 20 seconds better than Grahame-White's and he completed his nineteenth lap after 52 minutes 49.6 seconds in the air, Grahame -White having completed the 20 lap course in 1 hour 1 minute 4.47 seconds. However half-way round the last lap Leblanc's engine stopped, either through fuel shortage or the breakage of a fuel line, and he had to make a forced landing, colliding with a telegraph pole but fortunately escaping serious injury.

Meanwhile, Alec Ogilvie had been forced to land by engine problems after 13 laps after a delay of 54 minutes he took off again and eventually completed the course in a total time of 2h 26m 36.6s, good enough to gain him third place.

Walter Brookins

Walter Richard Brookins (July 11, 1889 – April 29, 1953) was the first pilot trained by the Wright brothers for their exhibition team.

Biography

Brookins was born in July 1889 in Dayton, Ohio to Clara Belle Spitler (1873–1947) and Noah Holsa ...

, flying the Wright "Baby Grand", was about to take off when Leblanc crashed, and decided to fly to the scene of the accident to see if he could help. However shortly after takeoff a connecting rod broke and his aircraft was wrecked in the subsequent forced landing. Brooking was unhurt. Hubert Latham

Arthur Charles Hubert Latham (10 January 1883 – 25 June 1912) was a French aviation pioneer. He was the first person to attempt to cross the English Channel in an aeroplane. Due to engine failure during his first of two attempts to cross ...

took off at 10:59, but his attempt was plagued by engine failures, and he spent about four hours on the ground making repairs, eventually completing the course in 5h 48m 53s, an average speed of .

Shortly before the latest permitted takeoff time John Drexel and John Moisant

John Bevins Moisant (April 25, 1868 – December 31, 1910), known as the "King of Aviators," was an American aviator, aeronautical engineer, flight instructor, businessman, and revolutionary. He was the first pilot to conduct passenger flight ...

, both flying Blériot IXs, started their attempts. Drexel was forced to retire after seven laps, while Moisant completed the course in 1h 57s 44.8s after landing more than once with engine problems, securing second place.

1911

The 1911 race was held on 1 July at theRoyal Aeronautical Society

The Royal Aeronautical Society, also known as the RAeS, is a British multi-disciplinary professional institution dedicated to the global aerospace community. Founded in 1866, it is the oldest aeronautical society in the world. Members, Fellows ...

's flying field at Eastchurch

Eastchurch is a village and civil parish on the Isle of Sheppey, in the English county of Kent, two miles east of Minster. The village website claims the area has "a history steeped in stories of piracy and smugglers".

Aviation history

Eastchu ...

, and attracted a crowd of around 10,000 spectators despite the comparative remoteness to the location. Both France and Britain entered three pilots with three reserves, the British entries including a Bristol Prier monoplane

__NOTOC__

The Bristol Prier monoplane was an early United Kingdom, British aircraft produced in a number of single- and two-seat versions.

Background

The Bristol Prier Monoplanes were a series of tractor configuration monoplanes designed for the ...

to be flown by Grahame Gilmour, but this was not ready in time to compete. The competition coincided with the Circuit of Europe The Circuit of Europe (''Circuit d'Europe'') was an air race held in 1911. A prize of £8,000 was offered by ''Le Journal (Paris), Le Journal'' for the entire Circuit, with additional prizes for the individual stages. The stages of the race totalled ...

air race, as a result of which the British pilot James Valentine withdrew: however Charles Weymann

Charles Terres Weymann (2 August 1889 – 1976) was a Haitian-born early aeroplane racing pilot and businessman. During World War I he flew for Nieuport as a test pilot and was awarded the rank of Chevalier of the Legion of Honour.

Early years ...

, the sole American representative chose to withdraw from the Circuit of Europe to take part in the Gordon Bennett competition.

The start of the competition was delayed by poor weather, and the first competitor Gustav Hamel

Gustav Wilhelm Hamel (25 June 1889 – missing 23 May 1914) was a pioneer British aviator. He was prominent in the early history of aviation in Britain, and in particular that of Hendon airfield, where Claude Graham-White was energeticall ...

, did not take off until 2:50 in the afternoon. Flying a Blériot XXIII

The Blériot XXIII was a racing monoplane produced in 1911 by Blériot Aéronautique. Two were built, both of which were flown in the 1911 Gordon Bennett Trophy (aeroplanes), Gordon Bennett Trophy competition at RNAS Eastchurch, Eastchurch; one, f ...

monoplane which had been modified shortly before the race by having its wings cut down by about a metre (39 in), he misjudged his first turn and crashed at high speed, astonishingly escaping without serious injury.Villard 1987, p. 122 At 3:00 Louis Chevalier, flying a Nieuport II

The Nieuport II was a mid-wing monoplane racing or sport aircraft built by the Société Anonyme des Établissements Nieuport between 1910 and 1914 and was noted for its high performance using a small twin-cylinder engine, and winning many ra ...

powered by a Nieuport engine. After five laps his engine began showing signs of trouble and he was eventually forced to land after eleven laps, damaging his undercarriage. He then resumed his attempt flying a replacement aircraft, but this also suffered an engine failure shortly after takeoff and he was forced to withdraw. Weymann took off at 3:45, impressing spectators by the steepness of his banked turns, shortly followed at 4:47 by Alec Ogilvie, flying the aircraft in which he had finished third the previous year, now powered by a 50 hp N.E.C engine. Last to take off were Edouard Nieuport and Alfred Leblanc

Alfred Leblanc (13 April 1869 – 22 November 1921) was a pioneer French aviator.

Biography

He was born on 13 April 1869 in Paris. In 1888, he became the technical director of the Victor Bidault metal foundry. A keen sportsman, he was an ener ...

. Leblanc was recovering from influenza and, probably made cautious by Hamel's crash, did not take the corners as sharply as Weymann, and Nieuport's aircraft, with a less powerful engine that Weyman's, was clearly not in serious competition.

1912

The 1912 race was held on 9 September in Clearing, Illinois. The race was 30 laps around an elliptical course, for a total distance of . As none of the U.S. aircraft available to fly that day could exceed , and with Védrines practice flights averaging far better, a French win was expected prior to the start of the race.1913

The 1913 event was held between the 27–29 September, 1913 at the Aerodrome de Champagne nearRheims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

, France.

1920

See also

*List of aviation awards

This list of aviation awards is an index to articles about notable awards given in the field of aviation. It includes a list of awards for winners of competitions or records, a list of awards by the Society of Experimental Test Pilots, various oth ...

* National Air Races

The National Air Races (also known as Pulitzer Trophy Races) are a series of pylon and cross-country races that have taken place in the United States since 1920. The science of aviation, and the speed and reliability of aircraft and engines grew ...

* Schneider Trophy

The Coupe d'Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider, also known as the Schneider Trophy, Schneider Prize or (incorrectly) the Schneider Cup is a trophy that was awarded annually (and later, biennially) to the winner of a race for seaplanes and flying ...

References

Bibliography

* Casey, Louis S. ''Curtiss: The Hammondsport Era, 1907–1915''. New York: Crown Publishers, 1981. . * Villard, Henry Serrano ''Blue Ribbon of the Air''. Washington: Smithsonian Press, 1987. {{ISBN, 0-87474-942-5.External links

Air Racing History - ESPA Racing

The Big Race of 1910 , Air & Space Magazine

Air races Air racing Aviation awards Bennett family Newspaper events 20th-century awards Sports trophies and awards